June 12, 2019: What I witnessed on the Hong Kong protest movement's first violent day

Predictable spoiler: The police attacked first in what appeared to be a planned assault, then lied about it.

My articles on Hong Kong legal and political issues are freely available to all, but the effort is sustained by monthly and annual donations from readers. If you find these articles worthwhile, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support ongoing work on this newsletter. Thanks for your support.

Hong Kong’s protest movement is often referred to abroad as a democracy movement. It is true that universal suffrage was, and is, one of Hongkongers’ goals. But democracy was never the primary focus of the 2019 protests. After initial protests against an onerous bill that would have allowed Hongkongers to be extradited to the Chinese Mainland, attention shifted to police brutality and justice for its victims. Of the five demands made by the protesters, three were related to police and prosecutorial abuses, and all three initially stemmed from a single day of violence: June 12, 2019.

Sunday is the third anniversary of that day. Known in Hong Kong simply as 612 (luk-yat-yi in Cantonese), that afternoon the Beijing-controlled Legislative Council (or LegCo) was planning to force through the deeply unpopular extradition bill. In response, Hongkongers staged a general strike and organized a protest in front of the LegCo Building. The demonstration was authorized and largely peaceful, but police soon rushed in with batons and shields, and shot tear gas, rubber bullets and bean bag rounds into the crowd. Protesters were arrested, and countless people were injured. The police declared the event a riot, despite the fact that they instigated the violence themselves.

I was at the demonstration that day. This is what I witnessed.

Ominous signs from the outset

On June 12, I had some business to take care of at the Immigration Tower in Wanchai. Just a few days before, I had returned to Hong Kong after a couple of years studying Chinese in Taiwan. I didn’t attend the first anti-extradition protest the previous weekend, in which 1 million Hongkongers took to the street, but knowing I would be near the planned protest at LegCo in Admiralty, I brought along my camera equipment and decided to walk over. My goal was not to insert myself into the protests, but to photograph the event and do my small part to help share the protesters’ story with the world.

I walked from the Immigration Tower towards Admiralty—about a 15 minute walk. A block from the protest, I came across a large formation of police, armed and in riot gear. I posted a video to social media, and snapped some photos.

The scene was ominous. All reports so far were that the protests were peaceful, and the government had said that morning it would not interfere with demonstrations. So why were the police lined up and ready to attack, decked out in full riot gear?

The commander of the formation was a non-Chinese senior officer with a British accent. This was odd to me, as British police were rare by that point. I later learned that this man was Superintendent Justin Shave, a UK citizen. His name and face would come up often in the coming months as he vigorously led Hong Kong police troops in violent attacks against protesters all over the city.

Several brave Hongkongers pleaded with the police not to do anything rash, to think of the best interests of their city and its people. One man held a sign that said “For the next generation” in Chinese, and “Save the Kids” in English.

Later, I saw the police arrest the same man and take him away.

I continued walking towards the protest, and encountered thousands of peaceful demonstrators. I told some of the first people I met about the force gathered a block away. They said they were already aware, and told me police were also gathering on the other side of the protest near the LegCo entrance—surrounding the demonstration.

Anticipating the assault, protesters all around me were putting up barricades and wrapping their skin in plastic (a method to protect from tear gas). Some had brought helmets, goggles and umbrellas. In contrast to my own naivety, it was clear that many protesters had anticipated that the police might get violent.

I walked into the crowds and spotted a perch where I thought I could get some good pictures. It was up on a wall next to a construction site, across from the CITIC Building. I climbed up and filmed the chanting, peaceful crowd.

The police attack

Just a few minutes after I arrived, on the other side of the protest nearest to the LegCo building, police suddenly began shoving their way into the demonstrators with shields. In response, protesters began forming lines to pass umbrellas to the front, which those on the front line could use to create a shield wall of their own. These protesters had every right to be there—the protest was even approved by the government—and intended to see it through.

I turned to look behind me, and Justin Shave’s rear formation had also arrived. They were forming a long line with shields to stop anyone trying to pass by. The police had blocked off two sides of escape, while on the other two sides were blocked by buildings and Victoria Harbor. The crowd was trapped.

Suddenly, everything was chaotic. Police in the front near LegCo began attacking protesters, using huge shields to press their advance. The rear police formation maintained their line, preventing protesters from escaping. Protesters rushed defensive equipment to the front—umbrellas, railings, anything that could block the way. Others began throwing water bottles and whatever else they had at the advancing police line. I stayed on my perch and captured as much as I could on camera.

Out of nowhere, there was a loud bang. In front of me towards LegCo, the first round of tear gas sailed into the trapped protesters. Police in front of LegCo shot a dozen or more rounds of gas directly at the crowd. I realized things were going to get dangerous quickly, but snapped a few quick photos.

At this point, with tear gas beginning to burn my eyes and skin, I jumped down from the wall to find cover. From behind where Justin Shave’s formation was maintaining its line, I heard gunshots. As protesters tried to run back to escape the tear gas in front of them, Shave’s team was shooting rubber bullets at them and beating any who reached the lines. All around me, protesters were screaming in pain and panic.

There was nowhere to go. I stayed by the wall and a protester poured some water in my eyes.

Near me, protesters set up a first aid station. Injured demonstrators began to arrive, some choking on tear gas, others bloody and bruised from batons or rubber bullets.

I knew I needed to get out of the trap, and decided to take a gamble. As a foreigner with a large camera in my hand, I took a chance that they’d mistake me for a journalist. I approached the rear police line and held my camera up, then kept walking. No one tried to stop me.

Fury and shame

Once I got past the police line, I turned around and began taking photos again; if they had mistaken me for a foreign journalist, then I was going to take advantage of that opportunity. I took more pictures of Shave. But I couldn’t contain my anger. I shouted at him as I snapped photos: “Where are you from? Is it a place with human rights? What the hell is wrong with you?” I was only a few feet from him and he clearly heard me, but he turned his head away and ignored my questions.

Up to this point, Shave’s rear formation had not moved into the crowd. They only held the line and prevented anyone from escaping, while the police near LegCo pressed into the protesters. But now, they broke into three groups: two preventing protesters from escaping, and one preparing for a full on assault to supplement the assault from the front near Legco. They were going to squeeze the protesters further and further together—an incredibly dangerous maneuver, as it could cause a crush or stampede.

I documented their preparation, but was shouted at to leave before I could film their assault.

I was in shock, and I was furious. I realize now that I was naive, but at the time I had truly believed that Hongkongers—police included—would have respected the right of other Hongkongers to protest. With some exceptions, that’s what happened in the 2014 Umbrella Movement, and I was caught off guard by how different things were just a few years later.

I took a video at the scene and posted it to Instagram recounting what I had seen.

At this point, having been noticed and pushed out by the police, I thought the only thing I could do was try to document the faces of some of the cops who I had just witnessed violently suppress a peaceful protest. I was so upset that I kept yelling at each individual officer, asking if they were ashamed of themselves before snapping a picture. These were some of the faces I captured.

Later, the police would say that the protesters attacked first, and much of the media reported it without question. But from my perch on a wall, the events were clear—the protesters were peaceful until police stormed down and into the front lines. For anyone who doubts these videos or thinks the images might have missed something, ask yourself this: If the goal was to clear out a “riot,” why would they have formed a trapping wall on both sides of an authorized demonstration to keep protesters in? The intention was always to not only attack, but cause maximum pain.

There was simply no justification for what I saw the police do that day. It was, for me, the first of many instances over the following three years in which my belief in rule of law and the good faith of Hong Kong government personnel would be shaken, and eventually shattered. It was also the moment that I realized that this moment in history was going to be important, and that I needed to take part in it. From that point on, I would attend almost every protest with my camera and did my best to play a small part in documenting events.

It has been three years since 612. Hong Kong is a very different place now, brought to its knees by those who saw the violent suppression of the city’s people as preferable to giving up one inch of their power and privilege to the aspirations of the masses.

But we have not lost. To the contrary, I believe we are winning.

For decades, despite abuses in Tiananmen, Tibet, Xinjiang, and elsewhere, nothing the Chinese Communist Party did seemed to alter the steady march of Western investment, intertwining of economies, and rocket-like growth. But Hong Kong did. Countless images of police abuses were broadcast almost in real time, while at the same time reports of government intransigence and incompetence blew a big hole in the world’s assumption that the rise of CCP authoritarianism was inevitable. While there is still much work to do, the developed world has shifted, slowly but surely, to a policy of containing the Chinese State and decoupling from its economy. There are many factors that contributed to this shift, but Hong Kong was the turning point.

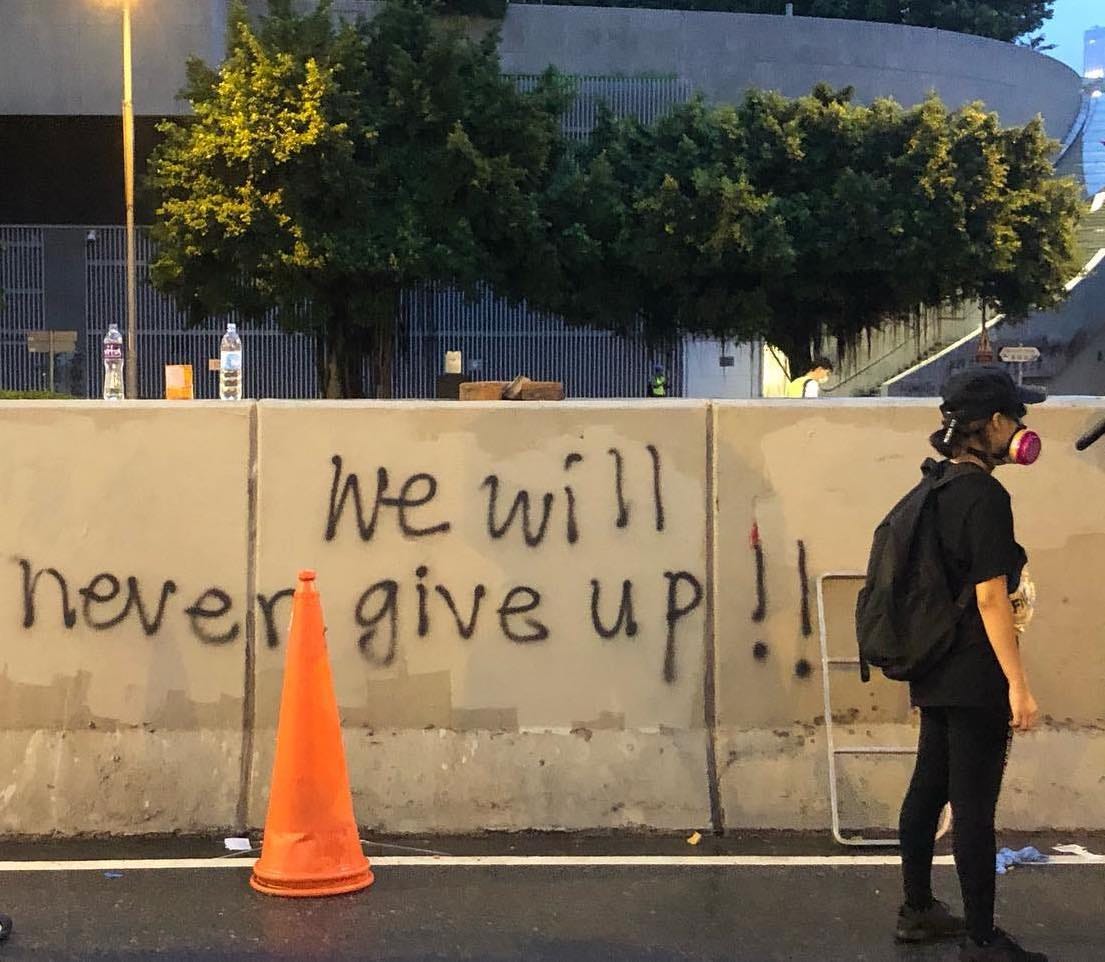

As we reflect and remember in Hong Kong and across the world for yet another year, and as we dread the coming series of sad anniversaries that we go through every summer, the memories can bring on a feeling of deep hopelessness. But Hongkongers will never give up on the city, and I truly believe that one day we will all gather in front of the LegCo once again.

When you asked those police officers if they were ashamed of themselves, the problem is they might not even understand what you were saying

Thank you for spreading the truth.