In the Court of Final Appeal's most recent national security judgment, there's more than meets the eye

A decision on mandatory minimums that seemed at first glance to play by Beijing's rules holds a few surprising signs of pushback within

My articles on Hong Kong are freely available to all, but they take a lot of time and effort to write. I greatly appreciate monthly or annual donations to sustain my work. You can sign up on Substack to support this work for US$8/month or US$80/year. You can also support my broader Hong Kong advocacy by subscribing at a variety of levels to my Patreon, where I post reflections and updates on my advocacy work. I’m grateful for your support.

Lui Sai-Yu was only 23 when he was arrested in September 2020 for operating a Telegram chat group supporting Hong Kong independence. After 19 long months in prison awaiting trial, he decided to end the ordeal by pleading guilty in return for a sentence reduction. But instead of reducing his sentence by the standard one-third, the plea earned him barely a 10 percent reduction, from 5.5 years to 5 years.

The reason? A mandatory five-year minimum sentence stipulated by the Hong Kong National Security Law (NSL) under which he was charged.

On Tuesday, Hong Kong's Court of Final Appeal (CFA) rejected Lui’s second appeal challenging this sentencing restriction. Lui’s chances of success were slim. Mandatory minimum sentences are virtually unprecedented in Hong Kong law, but the NSL’s language imposing them is clear. Since the judiciary long ago acceded to the NSL as the law of the land, there was little chance its plain terms would be rejected now.

Yet surprisingly, in other aspects of its ruling, the Court of Final Appeal took the opportunity to challenge certain of the more extreme pro-Beijing sentiments within the judiciary, particularly the intermediate-level Court of Appeal: It emphasized the importance of rehabilitation in sentencing, challenged the notion that Mainland laws should guide NSL interpretations, and underscored the court’s right to weigh mitigating factors beyond those explicitly mentioned in the NSL.

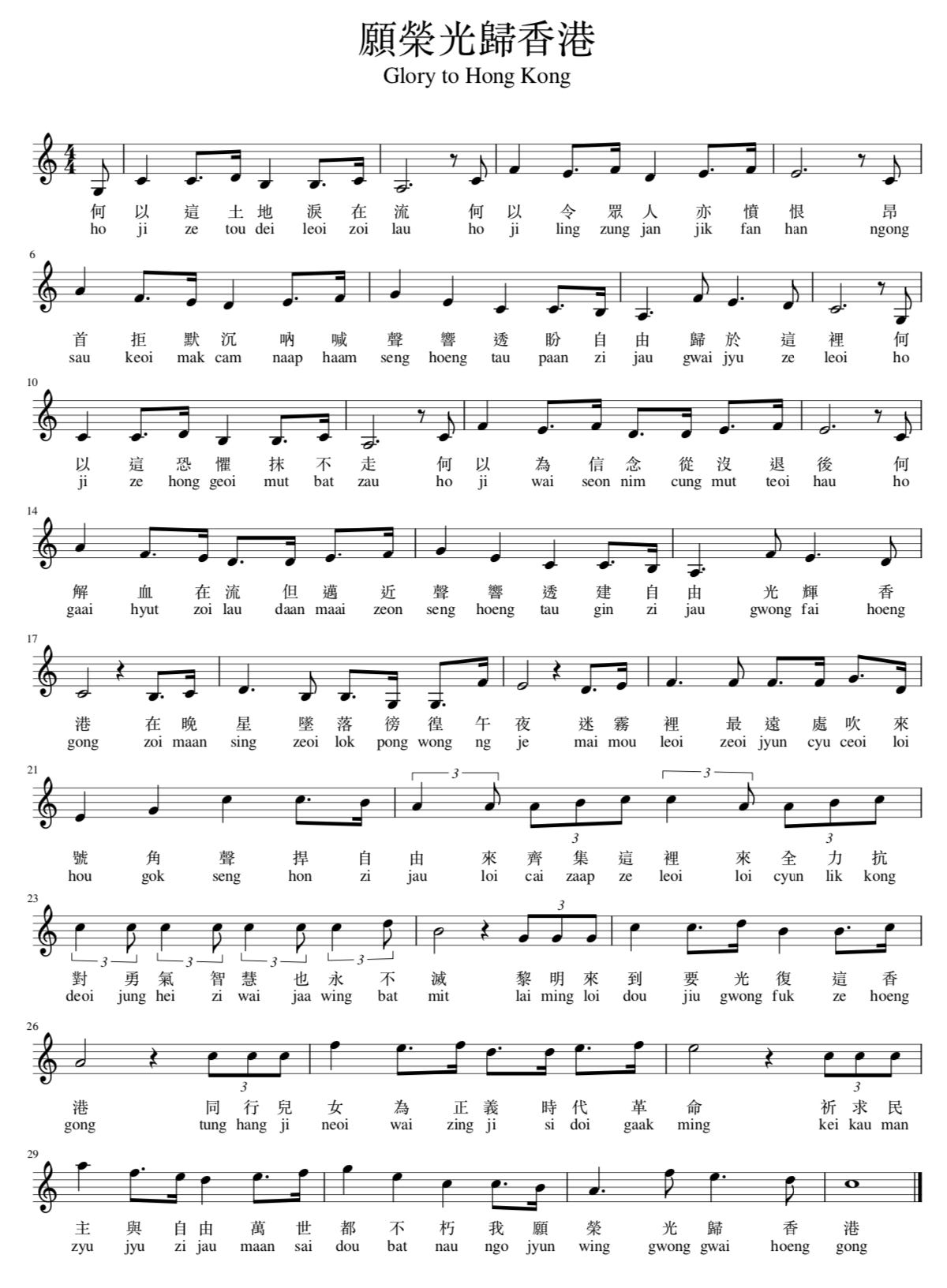

While these positions won’t help Lui get out of prison any sooner, they could open the door to better outcomes in other NSL cases, such as for non-core defendants in the ongoing subversion trial against 47 members of the democratic opposition and the DOJ’s legal effort to erase the protest song “Glory to Hong Kong.”

The CFA’s judgment, while endorsing the NSL overall and carefully avoiding a direct challenge to Beijing or local national security authorities, could signal an increased willingness on the court to push back on the fringes—or it could be an aberration. Only time will tell.

The case against Lui Sai-Yu

Lui and his mother were detained at their home in September 2020. Initially, the police accused them of arms dealing, but this turned out to be an exaggeration. The actual charge against Lui, for incitement to subversion, was limited to running a Telegram group that supported Hong Kong independence and facilitated the trade of protest gear. Like most national security defendants, Lui was denied bail, forcing him to remain in detention until trial.

National Security Judge Amanda Woodcock issued Lui’s sentence at the District Court in April 2022, after Lui had already been in prison for 19 months. In sentencing, Article 21 of the NSL requires judges to determine whether a secession case is “serious” or “minor.” If it is found to be minor, the person can receive up to five years imprisonment. If the matter is “serious,” however, the person is to be imprisoned for “not less than five years but not more than ten years.”

Despite the absence of any violence on Lui’s part or evidence that Lui incited any actual secessionist acts, Judge Woodcock labeled Lui’s offense as "serious." (The CFA’s Appeal Committee refused to grant leave to appeal the validity of this determination, so it was not considered in Tuesday’s judgment.)

Having established that the case fell into the “serious” sentencing range of 5-10 years, Judge Woodcock set the starting sentence at 5 years and 6 months. Accounting for Lui’s guilty plea, she intended to reduce it by the usual one-third, settling at 3 years and 8 months.

However, the prosecution quickly contested this, referencing the NSL’s mandatory five-year minimum for "serious" secession crimes. Judge Woodcock accepted this argument and revised her decision to a firm 5-year sentence.

Lui, with his legal team, challenged this sentence at the Court of Appeal, which affirmed the five year mandatory minimum. He then asked the CFA to hear the case, which agreed to consider two pivotal questions regarding mandatory minimum sentences. Both questions, while framed around technical points, sought clarity on whether the mandatory minimums are non-negotiable, or if judges still have leeway to sentence outside the range.

Why mandatory minimums are controversial in Hong Kong

The use of mandatory minimums in sentencing varies considerably across the world. In the United States, they are prevalent, whereas in many common law jurisdictions like Canada and the UK, they are used sparingly. In Mainland China, they are especially common, with a wide range of crimes prescribing “fixed term” imprisonments within a minimum and maximum range.

Hong Kong historically has not used mandatory minimums, and the judiciary has enjoyed broad latitude in sentencing. Some drug laws and sentencing practices come close to being mandatory, but still ultimately preserve judicial discretion. The NSL, however, imposed Mainland sentencing practices on Hong Kong, including mandatory minimums. Each of the NSL’s four offenses include tiers of severity with accompanying minimum and maximum sentence limits.

While not particularly unusual in a global context, in Hong Kong these mandatory minimums are seen as just one of Beijing’s many encroachments on the traditional independence of the courts. They disincentivize guilty pleas for many defendants, especially those—like Lui—who expect to be sentenced at the lower end of one of the NSL’s sentencing ranges. Even taken separately from the overall repressive nature of the NSL, mandatory minimums simply don’t work well in the context of Hong Kong’s justice system, where mitigation practices seek to promote the administration of justice.

The CFA’s ruling: mandatory minimums are indeed mandatory

Despite the controversy, there was little suspense surrounding the CFA’s judgment on this question. The NSL violates Hong Kong’s Basic Law and treaty commitments and is an astoundingly repressive law, but the courts have long accepted its authority. And if the NSL is the law of the land, its provisions on minimum sentencing were almost certainly meant to be obligatory. The English translation of the relevant portion of NSL 21, with emphasis added, reads:

“If the circumstances of the offence committed by a person are of a serious nature, the person shall be sentenced to fixed term imprisonment of not less than five years but not more than ten years.”

The official Chinese version, reflecting Mainland China’s customary legislative style, is more succinct: “情節嚴重的,處五年以上十年以下有期徒刑”—literally translated, “in serious circumstances, sentence not less than five years, not more than ten years.”

Both versions unmistakably indicate a mandate rather than mere guidance.

NSL Article 33 lists three exceptions where judges can reduce sentences below the mandatory minimum, but these exceptions do not include a guilty plea. The defense argued that the exceptions were not meant to be an exhaustive list, but neither the English nor Chinese version of Article 33 include any indication that the list is open-ended.

Consequently, although there is plenty to fault in the CFA’s recent handling of NSL and political disputes, their interpretation of these specific provisions appears accurate.

To be clear: The CFA’s ruling does not outright prohibit guilty plea sentence reductions in NSL cases. As discussed in the next section, the Court of Appeal had implied that the NSL bars most mitigation outright, including guilty plea reductions, but the CFA rejected this position. Rather, the NSL’s mitigation restrictions only apply where the sentence reduction would cause the total sentence to be reduced below the mandatory minimum.

Thus, despite his guilty plea, Lui was stuck with a 5-year sentence. This result is at odds with Hong Kong’s common law foundation and unjust, but therein lies the crux: The NSL was crafted in Beijing by officials who disdain Hong Kong’s common law heritage. The NSL is a Chinese law imposing Chinese legal norms on a system not designed for them.

A silver lining within—The CFA challenges the Court of Appeal’s excesses

Though the CFA’s decision on mandatory minimums was anticipated, the Court also took the opportunity to sharply criticize the Court of Appeal for some of it’s more extreme pro-Beijing positions. These surprising portions of the judgment could lead to reduced sentences for some NSL defendants if lower court judges properly heed the CFA’s direction—far from a certainly in the current environment, but room for cautious hope nonetheless.

The Court of Appeal, Hong Kong’s intermediate appellate court, rejected Lui’s first appeal last year In recent years, under the leadership of Chief Judge Jeremy Poon, this court has gained notoriety for its severe and sometimes illogical decisions against political defendants. Examples include a case in which it ruled that acts as benign as liking a social media post about a riot can potentially make a person liable for rioting themselves, denying jury trials to national security defendants under the pretext of “juror safety,” and a remarkable streak of granting 19 applications from the Department of Justice to increase sentences against 2019 protest defendants—then rejecting the twentieth only due to procedural delays.

Consistent with this track record, the three-judge panel of Chief Judge Poon alongside appellate judges Anthea Pang and Derek Pang, in ruling against Lui’s appeal, went well beyond the limited scope of the appeal and sought to significantly extend the repressive reach of the NSL. The CFA, apparently recognizing the significance of these issues, felt compelled to directly address three instances of overreach in the Court of Appeal’s judgment.

1. Court of Appeal: The national security “imperative” means most forms of mitigation are not allowed.

In an alarming segment of the Court of Appeal's ruling, the court declared that the NSL's significance was so profound that it ought to overshadow all other judicial considerations. With respect to guilty pleas and other sentencing mitigation, the judgment asserted that the NSL’s “Primary Purpose” of safeguarding national security is paramount, and as such, “not all mitigating circumstances are applicable. Only those which do not compromise the Primary Purpose are applicable.”

Applying this logic, the court went on to conclude that the only applicable mitigants were the three specifically listed in NSL Article 33—all of which relate to cooperating with the authorities. (CA Op, Pgh. 59).

If taken at face value, the Court of Appeal’s position would bar mitigation factors like pleading guilty, age, or remorse even in cases where the mandatory minimum isn’t an issue. If implemented, this interpretation would eliminate the vast majority of sentencing reductions, including guilty plea reductions.

The Court of Appeal isn’t the only body that has asserted recently that the NSL’s supreme importance should outweigh all other considerations. The DOJ recently made a similar argument in its pending appeal to obtain an injunction banning the protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong.” In a draft court filing, the DOJ asserted that the importance of national security is so high that the courts should largely defer to the government on such matters:

“It is wrong in law for the learned Judge to merely accord ‘significant weight’ to matters of national security, when they are matters of ‘the highest importance.’ …Unless the Court considers that the Injunction would not have any effect in assisting in the prevention or suppression or imposition of punishment against the 4 Acts [prohibited by the NSL], the balance should be in favor of granting the injunction.”

(Emphasis added.)

The CFA on Tuesday flatly rejected the idea that the NSL’s importance requires such extreme deference. Addressing the principle’s application to sentencing mitigation, the CFA wrote:

“It is hard to see how what has been defined as ‘the Imperative’ [the primary purpose of safeguarding national security] should lead to the conclusion that ‘not all mitigating circumstances are applicable’. It is also difficult to see what mitigating factors should or should not be available. Which factors should be regarded as ‘those which do not compromise the Primary Purpose’? … As part of the sentencing exercise, the court must determine the appropriate nature and level of sentence and, in doing so, takes into account both aggravating and mitigating factors as well as the individual’s circumstance. The entire process represents implementation of the ‘Primary Purpose’. It is therefore not easy to see how any specific mitigating factor…may be regarded as ‘compromising the ‘Primary Purpose’’.”

(CA Op., Pgh. 39).

In short, the CFA made clear that the courts still have the power—and obligation—in NSL cases to weigh different considerations beyond just national security. Whether this directive will actually improve outcomes in the “Glory to Hong Kong” appeal and separate criminal cases is less clear, but it at least appears to nip in the bud one of the most pernicious arguments advanced recently by the DOJ and Court of Appeal.

2. Court of Appeal: Rehabilitation should not be a consideration in sentencing national security defendants

In a portion of its decision that appeared to come out of nowhere, the Court of Appeal announced that the NSL required deviating from the so-called classical principles of sentencing—deterrence, retribution, prevention and rehabilitation. Specifically, the court replaced the rehabilitation principle—which focuses on equipping convicted defendants with the skills and resources necessary for societal reintegration—with “incapacitation,” which the court described as “putting out of the power of the offender to commit further offences.” The court labeled this revamped approach as the “Penological Considerations.” (Pgh. 57)

The CFA rejected this approach. After expressing some confusion over the Court of Appeal’s rationale for this decision, the CFA wrote:

“A glaring omission from the Court of Appeal’s ‘Penological Considerations’ is the principle of rehabilitation.

…As a matter of principle…rehabilitation should not be omitted or excluded as a sentencing principle when giving effect to NSL21. Indeed, NSL21 expressly recognises that an offence may be ‘of a minor nature’ and that the person concerned might be sentenced ‘to fixed-term imprisonment of not more than five years, short-term detention or restriction’. Given those sentencing options, in a particular case a court might well think it appropriate to give weight to the objective of rehabilitation by imposing a short, training-oriented sentence or a non-custodial sentence as the best means of protecting society.”

(CFA Op. Pghs. 36-37).

Besides underscoring the evident fact that the NSL doesn’t prohibit applying rehabilitation principles in sentencing, the CFA’s explicit reference to non-custodial sentences may offer hope to some current defendants, such as the minor players in the ongoing Hong Kong 47 case. In the current hyper-politicized environment, many judges and magistrates seem afraid to take any step that might draw accusations from Beijing of being too light in sentencing political dissidents; thus far, every NSL defendant has received a custodial sentence. But this declaration from the CFA endorsing lighter or alternative sentences may open the door ever-so-slightly to less severe outcomes in “minor” cases.

3. Court of Appeal: Courts can rely on other Mainland laws to interpret the NSL

During oral arguments at the Court of Appeal, the prosecution sought to rely on separate Mainland Chinese sentencing laws to support its arguments. Leveraging Mainland Chinese law as a basis for judgments and sentences in Hong Kong would represent a significant departure from the established norms, given the marked differences between the two legal systems. (The Mainland system is still more repressive in many ways, despite the rapid deterioration of Hong Kong’s system.) Yet, the Court of Appeal concluded that it was appropriate to consider the Mainland law in interpreting the NSL—including for sentences. (Pghs. 87-89)

The CFA rejected this position, asserting that the scope of “extrinsic materials which are admissible in aid of construing the NSL” is considerably more limited. “Separate pieces of Mainland legislation which were enacted in a different context and for general purposes differing from and lacking any connection with the context and purposes for which the NSL was promulgated” cannot be used to support a Hong Kong court ruling.

This finding is potentially good news for some NSL defendants. Within the prescribed sentencing ranges stipulated by the NSL, judges retain a considerable degree of discretion. For some of the gravest offenses—subversion “principal offnders”, for instance—the prescribed sentencing range is ten years to life imprisonment. In the Mainland, similar offenses often lead to verdicts skewing closer to life sentences or even death sentences, whereas in Hong Kong, precedents and prevailing norms might push sentences closer to the ten year mark. By rejecting consideration of Mainland law, the CFA may be avoiding a surge in sentence durations that such an integration could precipitate.

***

Hong Kong's current legal climate is riddled with constraints. Bold, direct confrontations with the regime, even when legally justified, are challenging to navigate. This was evident, for example, when Beijing swiftly overturned the CFA's decision to allow Jimmy Lai to hire a foreign lawyer. Such interventions from Chinese authorities are a reminder that the overarching power dynamic skews strongly in Beijing’s favor, but exercising these powers comes with a reputational cost to Beijing. Consequently, for those remaining judges who genuinely want to preserve what’s left of their autonomy, a more tactful approach focused on creating space on the margins may be the best way forward.

Since the passage of the NSL, the courts has been largely ineffective in defending—and at times complicit in dismantling—Hong Kong’s legal and constitutional norms. But there have been recent signs of pushback from a few judges. Time will tell if these rulings are an aberration, or a genuine shift towards subtly drawing a few lines in the sand.