Hong Kong’s new “Article 23” security law: Extending China's shroud of secrecy over Hong Kong

New state secrets and foreign interference offenses will adopt Mainland China’s approach to information control, while eliminating even more rights for political defendants.

A new security law, verdicts against Jimmy Lai and the Hong Kong 47, a court battle over censoring ‘Glory to Hong Kong’: In 2024, there will be good reasons to keep the world’s attention on China’s crackdown on Hong Kong, and I’ll be providing analysis and advocacy—both online and offline—for each and every development. Are you able to support my efforts? You can contribute to my work either via a subscription to this Substack or my Patreon. Only do so if you’re comfortable with the risks involved in supporting this movement. I’m grateful for your support.

Since Beijing imposed the notorious National Security Law on Hong Kong in July 2020, nearly three hundred of the government’s political opponents have been arrested, civil society has been silenced, dozens of media outlets have been shuttered, hundreds of thousands of people have fled the city for the UK and other democracies, and the economy has sputtered.

But in Beijing’s eyes, the NSL wasn’t enough. On Tuesday, Hong Kong’s Security Bureau (HKSB) released details of the long-anticipated new “Article 23” national security law. The law will supplement, not replace, the 2020 NSL. It will be passed into law locally this year. (The 2020 NSL, in contrast, was imposed directly by Beijing, though in practice Beijing is controlling the Article 23 process as well.) The specifics are contained in a 110-page “public consultation” document that commences a 30-day consultation period on the law.

Among those who cherish Hong Kong’s traditional openness and autonomy, there has been much speculation about the best- and worst-case scenarios for the legislation. Unfortunately, this week’s proposals come closer to the worst of those predictions. The HKSB showed little restraint, adopting almost wholesale some particularly repressive portions of the Mainland Chinese security and secrecy regime, and proposing to eliminate even more procedural protections for defendants. Even pro-Beijing Hong Kong officials like Executive Council member Ronny Tong and lawmaker Dominic Lee have voiced concerns about the proposals.

Typically, the consultation period for new laws is 2-3 months. A 30-day period is not unprecedented, but it is particularly short. It signals—unsurprisingly—that few, if any, modifications will be made in response to public concerns. HKSB chief Chris Tang may give lip service to lawmaker concerns, as he did today in response to Dominic Lee during a LegCo session, but it’s likely that Beijing has already signed off on the features of the new legislation. While we may see minor tweaks, we can expect these draft proposals to remain largely unchanged.

When implemented, this legislation will severely restrict, if not eliminate entirely, Hongkongers’ already-limited freedoms to speak out against their government, monitor officials and their departments for corruption and misconduct, obtain information from officials, and even to share their views with friends and family in private. As the proposals explicitly state, their goal is to fully align Hong Kong’s security regime with the repressive and comprehensively secretive Chinese security state. China’s crackdown on Hong Kong will continue well past this law’s implementation, but our window to witness it happening may be closing.

I provided some brief preliminary thoughts on the proposals via social media shortly after their release. Having now had time to assess the document in more detail, I want to highlight a few of the most worrisome portions.

Hong Kong to adopt China’s “state secrets” regime

State secrets legislation is explicitly required by Article 23 of the Basic Law, but there are a range of ways the law could define state secrets. The committee chose the most repressive option—adopting Mainland China’s own definition in full.

China’s Law on Guarding State Secrets defines state secrets extraordinarily broadly to include not just top secret security matters such as national defense and diplomatic information, but also economic data, science and technology materials, and “other matters classified as state secrets by the National Administration of State Secret Protection”—essentially, anything that the government wants to designate as a state secret. What’s more, the law includes an even broader category of restricted information called “Internal Matters,” which are not classified as state secrets but are nonetheless internal and cannot be disclosed without regulatory authorization.

The proposed definition of state secrets largely adopts the Chinese definition, and also would impose tiers of confidentiality similar to the Chinese law. This allows the government to restrict access to virtually any government-held information, sensitive or not. In justifying this, HKSB points to the need for consistency with the Mainland, writing: “All types of state secrets should be protected in every place within one country…Protecting state secrets is particularly important to protecting national security and core interests, and is a matter within the purview of the Central Authorities.”

But this is clearly incorrect. Article 23 itself—the Basic Law provision that launched this whole process—explicitly mentions state secrets as falling within the purview of the Hong Kong authorities, not Beijing. HKSB’s explanation is a weak attempt to legally justify what is, in all likelihood, a decision made by authorities in Beijing—not Hong Kong—to expand the Mainland security regime to the city.

It is impossible to know yet how strictly Hong Kong will enforce the Chinese state secrets regime. But some recent China “state secrets” cases may serve to illustrate what Hong Kong is facing:

Swedish citizen Gui Minhai was abducted by Chinese agents in Thailand in 2015 and illegally brought back to the Mainland, where he was accused of publishing books in Hong Kong that included “state secrets.” Gui’s books contained tabloid-style gossip on topics such as extramarital affairs and corruption among Chinese officials. He was denied consular assistance and sentenced to ten years in prison.

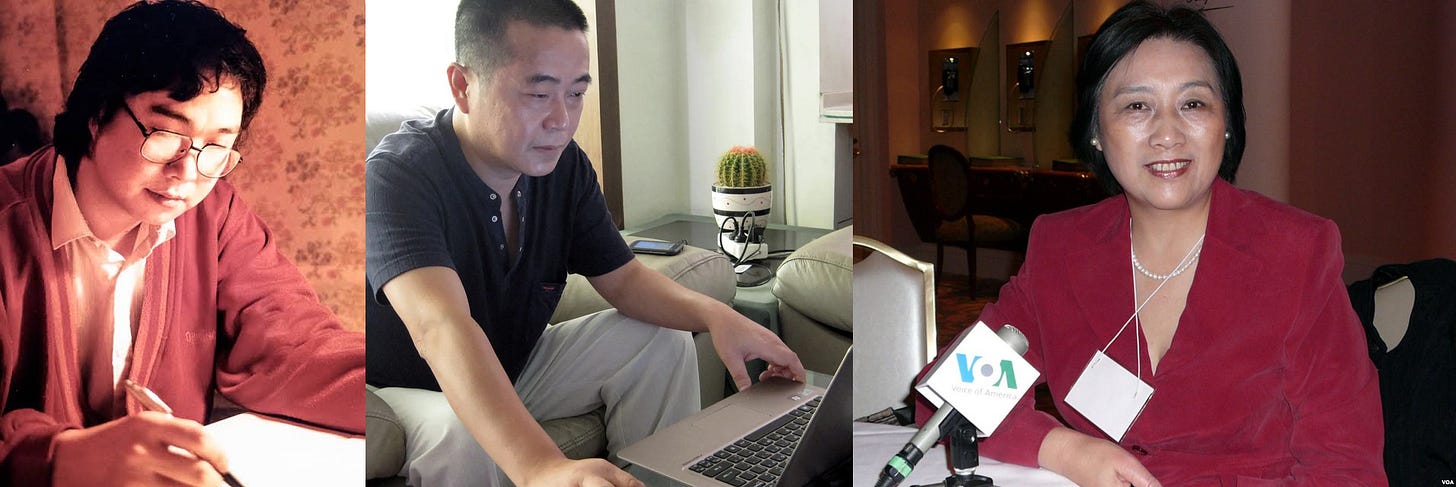

Huang Qi, founder of the advocacy website 64 Tianwang, has been imprisoned multiple times for theft of state secrets for reporting on matters such as the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, and a woman who self-immolated in 2014 as protest at the start of that year’s National People’s Congress.

Gao Yu, a longtime journalist, was sentenced to 7 years in prison in 2015 for leaking “state secrets.” She was accused of disclosing a Communist Party directive, the infamous “Document No. 9,” that had already been widely summarized on government websites.

Given Hong Kong’s role as a financial center with an open economy that the world—including Mainland China—relies on heavily for trade investment, it would make little sense to impose such a repressive state secrets regime on the city. But that’s exactly what the HKSB is proposing. The law is likely to further depress already low investment and trust in the city by international investors and financial firms—the lifeblood of the city’s economy.

Whatever the long-term prospects for this new law to be used to imprison dissidents and journalists, in the immediate term the most noticeable change we may see is government departments locking down public access to their operations and officials. Since the 1990s, the Code on Access to Information has underpinned Hong Kong’s liberal open door policy among most government departments, allowing for journalists, investigators, and ordinary members of the public to request and receive information and documents promptly on request. It is hard to see how the Code and other open government policies could survive the imposition of China’s state secrets regime.

The continued obsession with “external interference”

The HKSB proposals are preoccupied with foreigners in Hong Kong, whether foreign governments, foreign human rights organizations, or ordinary gweilos. This is consistent with the regular attacks on foreigners launched by HKSB and Security Secretary Chris Tang, but it is still surprising how frequently paranoia shines through in this formal public consultation document.

The phrase “external forces” appears 43 times, while “colour revolution” appears twelve times. At one point in Chapter 7, HKSB declares:

“External forces have been using the HKSAR as a bridgehead for anti-China activities, and have been assisting and instigating local organizations or individuals to cause social instability under different pretexts, and propagating anti-China ideology through a soft approach to demonize the [Central People’s Government] and the HKSAR Government.”

This section goes on to specifically call out “non-governmental bodies”—NGOs—and claims they are “actually established by external forces or have close ties with external forces.” As an example, it paints “human rights” NGOs as “external forces” and claims that these groups are instigating “resistance activities” and “colour revolution.”

In other words, the document reflects the government’s—and Beijing’s—ever-expanding conspiracy theories about foreigners and their intentions for China. It also unintentionally reveals the low opinion the government has of its own people by implying that Hongkongers could never have been thoughtful and sophisticated enough to develop their own views about democracy and human rights without foreign puppet masters.

The reality, of course, is that foreign NGOs and individuals represent not a threat to stability of the city, but to the Communist Party and Xi Jinping. “Anti-China activities” in this context really means anyone or anything from outside that might suggest to Hongkongers that there are better alternatives than the Party’s totalitarianism. Make no mistake: When the HKSB’s proposals talk about stopping “external interference,” they mean full-fledged xenophobia. Their goal is to control the flow of outside information and ideas reaching their people’s eyes and ears.

The centerpiece of the crackdown on foreigners will be a new criminal offense of “external interference.” The law would prohibit “collaborating with any external force” to “influence…the formulation or execution of any policy or measure, or the making or execution of any other decision” by the Hong Kong or Chinese governments, as well as “prejudicing the relationship between the Central Authorities and HKSAR.”

In short, the law would make it a crime for any foreigner or foreign organization to critique in any way the government, political proposals, or Hong Kong society. Anything that might be seen as an expression of discontent against the “Central Authorities or the HKSAR” will be off limits for foreigners.

Hong Kong is an international city that is home to hundreds of thousands of foreign residents and hosts millions of foreign visitors each year. Its economy is reliant on an open climate in which global businesses and organizations depend on being able to—and frequently do—critique government regulations and policies, provide frank assessments of the local and Chinese economy, and collect reliable data from a range of sources. This law will eliminate their ability to safely do any of that.

Forcing friends and family to report ‘treason’

The proposals would codify the offense of “misprision of treason,” which would require any person to report suspected treason to the authorities. A similar crime existed in the common law. What will change here is that “treason” laws are also being rewritten to apply not just to levying war, but also to “threating to use force…with intent to endanger the sovereignty, unity or territorial integrity of China.”

This will compel Hongkongers to report on each other. “Use of force” is defined very broadly by HKSB. Elsewhere, for example, the document refers to the 2019 protests as the use of force, despite the vast majority of protesters remaining nonviolent or merely blocking roads or conducting vandalism.

This provision also poses significant dangers to the friends and family members of overseas activists, including many of my friends and colleagues here in the United States. If Hongkongers tied to these activists fail to report regularly on their activities, it could give the police grounds to arrest and charge them with misprision.

Stripping away remaining procedural protections

While I have thus far focused on the new laws being proposed, the HKSB also proposed a range of procedural “reforms” that would further restrict the rights of dissidents. These proposals, while vaguer on the details, are just as concerning as the proposed new offences.

The proposed revisions include allowing the police to seek extended detention of national security suspects without charging them. The proposal is vague on how long the police would be able to detain suspects, but in China, persons deemed national security threats can be held for up to six months in “residential surveillance.” Given the general approach HKSB is taking in syncing up Hong Kong’s laws and procedures to China’s, I would predict a similar length of detention would be proposed for Hong Kong.

The document also includes an ominously vague proposal for “eliminating certain procedures” in national security court proceedings. HKSB frames these proposals as relating to speeding up the time between arrest and trial, which if true would be admirable—but that would certainly be giving HKSB too much credit. Instead, this proposal will be used as a pretext for eliminating defendants’ rights in pre-trial and trial procedures, without similarly reducing or restricting any prosecutorial powers. These measures to “streamline” the process could include curtailing the right to committal proceedings, bail hearings, or even appeals.

Another proposal would eliminate for national security convicts the 1/3 good behavior reduction in sentence that can be awarded by Correctional Services to prisoners, unless HKSB finds that they no longer pose a threat to society. (Spoiler alert: HKSB will never find this.) Every single other prisoner is entitled to this sentencing reduction. I can think of little basis for this change except that the government just wants to be vindictive.

Finally, for “fugitives” overseas, such as my human rights colleagues listed on the Hong Kong “bounty” list, the government proposes empowering itself to take measures including revoking their passports, which would leave many of these individuals stateless. This piece of the proposal should be emphasized by activists to our friends in Western governments who continue to drag their feet in offering paths to residency and citizenship to Hongkongers.

***

We all hoped to see some moderation from the government in its Article 23 proposals, but one would have to be hopelessly naïve indeed to truly expect that to happen . There are elements within the government that would prefer to see this radically oppressive proposal never become law (Financial Secretary Paul Chan, whose job is to revive the economy, has probably screamed into a few pillows this week). But since the 2020 NSL and the 2022 appointment of John Lee, a national security official, as Chief Executive, Beijing has made it clear that national security—and national control—take primacy.

The Article 23 proposals are designed to extend China’s shroud of secrecy and control over Hong Kong. In the process, they are likely to not only eliminate the remaining vestiges of open government and a rights-based order, but also serve as a final nail in the coffin for Hong Kong’s prior status as a financial powerhouse and an open international city.