Battle cries and bluster: Decoding Hong Kong's reactions to proposed new U.S. sanctions

The ferocity of the response to the newly-introduced Hong Kong Sanctions Act is all bark and no bite, yet underscores the impact its passage could have on global perceptions of Hong Kong’s rule of law

Hong Kong Law & Policy is a free, public interest, reader-supported publication. My continued writing and advocacy are dependent on monthly and annual donations from supporters. You can support my work either by signing up on Substack for US$8/month or US$80/year, or by subscribing to my Patreon for a similar amount. Thank you for your support!

***

Last Thursday, a bipartisan group of five U.S. lawmakers introduced the Hong Kong Sanctions Act, a bill targeting 49 Hong Kong judges, prosecutors, and government officials for sanctions. Since then, Hong Kong and Beijing officials have responded with a level of fury that few anticipated. The reactions have ranged from outraged statements issued by a dozen official and semi-official bodies, full newspaper spreads in state media, and threats to retaliate against political prisoners by sending them over the border to China for secret trials.

Through all the noise, I want to focus on two important takeaways. (Full disclosure: As lawmakers developed this bill, I was involved in the consultations around its contents, though far from the most central player.) First, by reacting so forcefully, Hong Kong officials may have unintentionally made it more likely that this bill will gain momentum and pass. Second, the threats that have been made to retaliate against political prisoners are very likely to be bluffs: Acting on these threats wouldn’t make much sense strategically, and the three former officials who made the statements likely spoke off-the-cuff without Beijing’s blessing.

The Hong Kong Sanctions Act: A Brief Overview

U.S. sanctions have disproportionate impact on their targets because of the country’s central role in the international financial system, in particular the widespread use of the dollar in global transactions and reserves. As such, U.S. sanctions often don’t merely block targets from using American banks and doing business with American companies, but rather cut them off from most elements of the global financial system altogether.

The use of individual human rights sanctions can be controversial, even among the human rights community. Detractors argue that they have limited impact on the overall human rights situation in Hong Kong and elsewhere.

I tend to agree that advocacy orgs sometimes spend too much of their time and resources advocating for individual sanctions, but they do serve a purpose. They can, if handled smartly, deter not-yet-sanctioned officials from conducting abuses of their own in an effort to avoid being sanctioned themselves. Beyond that, they serve an important justice purpose: Hongkongers have little hope that these officials will be punished by their own government, but take some solace in the knowledge that they will still face consequences via foreign sanctions. Thus, I believe they are worth supporting and advocating for.

Two U.S. laws passed in 2019 and 2020—the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act and the Hong Kong Autonomy Act—require the President to impose sanctions on Hong Kong officials responsible for human rights abuses or undermining Hong Kong’s autonomy. The language of the bills is not optional—the President “shall” identify abusive officials and sanction them.

But after two initial, small rounds of sanctions shortly following each bill, both the current and previous U.S. administrations have failed to issue further sanctions as required by these laws.

The Hong Kong Sanctions Act seeks to remedy this failure. It was introduced in both the House and Senate by three Republicans and two Democrats—Representatives Young Kim (R-CA), Jim McGovern (D-MA) and John Curtis (R-UT), and Senators Dan Sullivan (R-AK) and Jeff Merkley (D-OR). For the 49 officials named, the bill does not directly impose sanctions; rather, it requires the President to report to Congress on whether each of the 49 people warrant sanctions under the two previous laws. If so, he must sanction them; if not, he has to justify to Congress in detail why he has not done so.

So ultimately, this bill balances Congress’ prerogative to compel the President to act with recognition that the administration is best equipped to determine if sanctions are appropriate.

With that said, it would be difficult for the administration to justify not sanctioning most of these 49 officials if they’re required to assess them. The names on the list were selected because of their direct participation in the rigged NSL trial process or participating in particularly egregious non-NSL political prosecutions, which global authorities including the United Nations Human Rights Committee have found to violate international human rights treaties. If this bill becomes law, most if not all the names on the list would likely end up on the sanctions list.

The flood of official statements against the Sanctions Act reveals authorities’ panic about its impact

It is common for the Hong Kong government to issue a single statement in response to actions by foreign legislatures that they disapprove of. But since the new sanctions bill’s introduction, the reaction has been far stronger. The statements flooding out of Hong Kong have come from a wide range of public and semi-public sources, ranging from the usual suspects like the Hong Kong government and PRC Liaison Office in Hong Kong, to significantly less expected ones like the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce and—inexplicably—the Real Estate Developers Association of Hong Kong.

In many cases, the statements have been rife with often amusing histrionics. Some refuse to even call the bill a bill or a sanction a sanction, prefacing their descriptions with qualifiers like “the so-called ‘bill’.” Others invoke war analogies or historical geopolitical wrongs to make their point. Here are some highlights, though I encourage clicking through to read the whole statements—honestly, they’re pretty entertaining.

Hong Kong Government – The government “condemned…the so-called ‘bill’” to include officials “in a so-called list of ‘sanctions’ in an attempt to intimidate the HKSAR personnel concerned who safeguard national security.” Hong Kong “despises any so-called ‘sanctions’ and shall never be intimidated.”

PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Hong Kong – “Intimidation cannot subdue the Chinese people.” The U.S. politicians’ “open clamor to sanction judges and other diligent SAR personnel fully reveals their bottomless hegemonic behavior and despicable intentions to create chaos and harm Hong Kong.”

PRC Liaison Office in Hong Kong – The U.S. politicians’ “poor political performance is doomed to backfire and be fruitless.” They “are heavily involved in political manipulation, openly imposing so-called ‘sanctions’ on officials [and] crudely interfering with Hong Kong’s judiciary, which is a great irony and mockery of their touted democracy and rule of law….The Chinese nation has an inherent nature of not fearing the powerful, becoming braver in the face of battle, and growing stronger in the face of adversity.”

Hong Kong Judiciary – Judiciary “strongly condemns…any attempt to exert improper pressure on Judges and Judicial Officers.” It is “a flagrant and direct affront to the rule of law and judicial independence in Hong Kong.”

The (“patriots only”) Legislative Council – These “despicable attempts by American politicians to interfere will undoubtedly be in vain.”

Law Society of Hong Kong – Law Society “strongly condemns any attempt to interfere with the administration of justice or challenge the rule of law, judicial independence, prosecutorial or governance integrity.” “Any attempt to exert pressure by the implementation of sanctions [against a judge or prosecutor due to their role]…is an affront to the rule of law and judicial, prosecutorial and governance integrity.”

Hong Kong Bar Association – “HKBA condemns in the strongest terms any attempts by anyone, anywhere, to impose sanctions on” judges and judicial officers. Sanctions are “improper interference with the administration of justice” and “go against the very spirit of the rule of law.”

Commissioner of Police – U.S. “hegemonism is doomed to fail.”

Committee for Safeguarding National Security – “Expresses strong indignation and vehemently condemns foreign politicians who spread various false narratives in their rowdy attempt to interfere in the duties of” Hong Kong officials.

Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, Hong Kong (Chinese only) – The Act is a “blatant act of bullying” and the Chamber is “outraged by the unfounded accusations.”

Real Estate Developers Association of Hong Kong (Chinese only) – the Association “strongly condemns any attempt to interfere with the judicial independence of Hong Kong.”

Some of the statements have been issued in Chinese only. Even the official Hong Kong government statement, which by law must be issued in both English and Chinese, was initially only issued in Chinese before an English translation later appeared. This suggests that while much of the language is seemingly directed towards the U.S. government, the domestic audience for these statements is just as, if not more, important to them.

Amidst these statements, to top it off, a Communist Party-owned newspaper in Hong Kong, Wen Wei Po, published a two-page full spread of articles and photos that sought to express outrage at the bill via a series of coordinated protests and interviews—with results that one could, if being charitable, describe as mixed.

In the spread, a large headline reads, “THE ENTIRE CITY PROTESTS AND ROARS, DENOUNCES U.S. POLITICIANS FOR MEDDLING IN HONG KONG AFFAIRS.” Accompanying the headlines are three photos of seemingly separate groups of mostly elderly people, holding coordinated signs in front of the U.S. Consulate. The grand total of people depicted in these “entire city protests” is, by my count, 45.

Not quite the 1-2 million strong who protested against the government in 2019.

If that weren’t enough, the newspaper spread includes five feature photos of “protesters,” all holding their fist out in front of them. One can only assume the photographer told them to shake a fist to look angry, but the expressions produced range from “I think I forgot to turn off the oven,” to “Who are you? Why am I here?” The whole production is truly a work of art.

Keep in mind: The government did not undertake this coordinated, barn-burning response of official statements, staged protests, and state media articles in response to a new U.S. law or policy. Rather, they did so in response to five members of Congress—out of 535—simply introducing a bill, just one of more than a hundred bills introduced this session alone related to China. So, what is it about this particular bill that has hit such a nerve?

Probably, like most such things, it comes down to money.

As China has further encroached on Hong Kong’s relative autonomy and freedoms, businesses have taken notice. Hong Kong has long been the most popular choice among multi-national corporations for their Asia headquarters because it offered the best of both worlds: easy access to the lucrative China market, while operating under the protection of a free economy with rule of law. Businesses need predictable laws and policies that reassure them that their profits won’t be affected by political meddling or biases.

And critical to this perception of Hong Kong as a reliable base of operations was the independence of the judiciary. As the Hong Kong government itself has stated, “Hong Kong’s commitment to the rule of law and judicial independence is key to the city’s prosperity and stability as an international financial centre.”

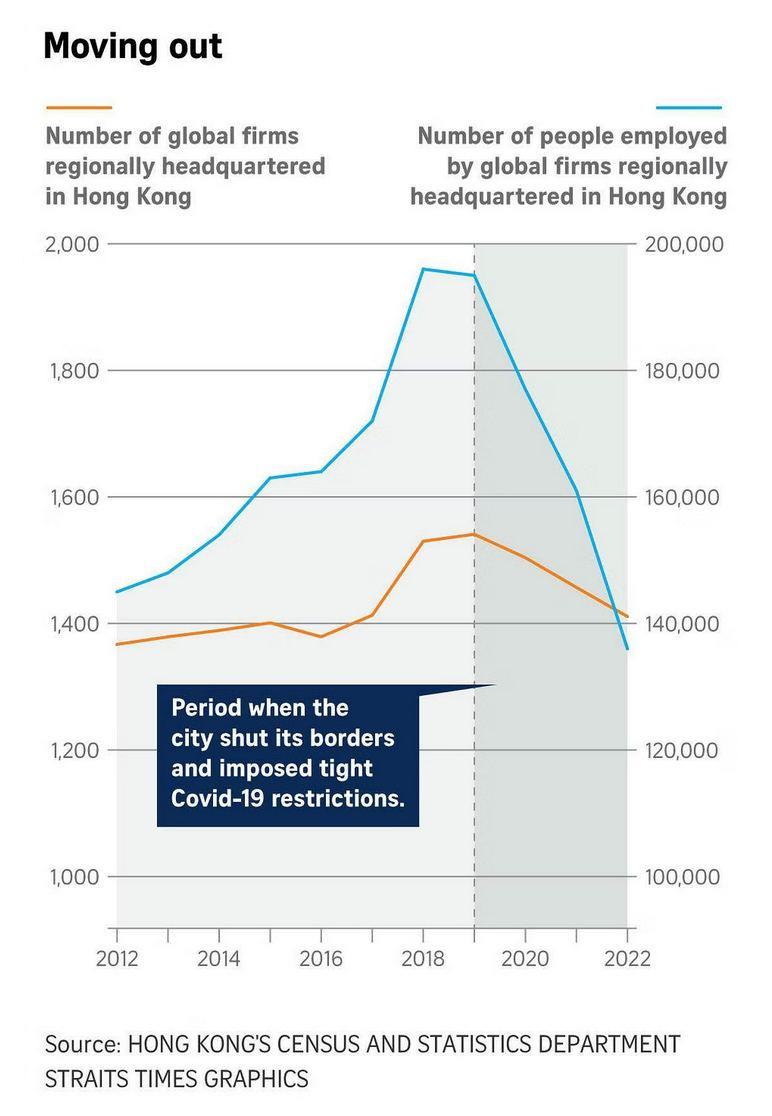

As serious doubts have set in about what China’s encroachment on Hong Kong means for these legal protections, many companies have begun moving personnel and assets away from the city. Since 2019, according to the Straits Times, the number of people employed by global firms regionally headquartered in Hong Kong has dropped by almost a third, from 195,000 to 135,000. This tracks with what I’ve been told by sources in Hong Kong financial and legal firms—that while officially moving their regional headquarters would be politically and financially risky, many firms are quietly shifting key headquarters staff to Singapore and other locations in the region.

There are other signs that global corporate leaders don’t see the city as the sure bet it once was. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that China-focused private equity investment via Hong Kong has declined 89% this year compared to last year, while IPOs on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange raised a mere US$3.5 billion, down 92% from the US$42.8 billion raised in 2021. While these drops are partly due to a global slowdown, The declines in Hong Kong far outpace the rest of the world.

In response to these signs of the city’s falling star, the Hong Kong government as acted forcefully to try to preserve its status. It has sent the financial and treasury secretaries globetrotting on multiple trips to wealthy countries to promote the city’s markets and supposed business-friendly legal system, while frequently reiterating its commitment to rule of law.

But the government can only do so much to hide the reality: Hong Kong’s judiciary is not, in fact, independent. In recent years, Beijing has exerted substantial and ever-increasing political control over the courts.

The 2020 National Security Law permitted the Beijing-appointed Chief Executive to appoint special judges to handle cases brought against political dissidents under the law. These national security judges soon extended the scope of the NSL to non-NSL laws, such as colonial sedition laws.

Then, in late-December last year, Beijing issued an “interpretation” of the National Security Law that overruled a final decision of Hong Kong’s highest court permitting imprisoned media figure Jimmy Lai to choose his own lawyer. But the interpretation went well beyond that. As I wrote at the time, Beijing used the opportunity to carve out a right to declare any act—whether taken by the courts, government officials, or private citizens—as involving “national security” and therefore under Beijing’s direct control. This power grab grants Beijing near-total authority to interfere with the courts at will, and it showed Hongkongers and business leaders that Beijing was willing to use that power.

The Hong Kong Sanctions Act seeks to punish the judges and prosecutors who have been complicit in Beijing’s destruction of the independent judiciary. And in doing so, the United States would make it more difficult for the Hong Kong government to paper over these abuses and attract investment back to the city.

Those calling the shots in Hong Kong and Beijing simply couldn’t tolerate this possibility. But in reacting so strongly to what could have been a relatively obscure bill, Beijing is just drawing attention to what it most wants to hide: that rule of law in Hong Kong has been severely compromised.

Threats to transfer prisoners to China if the bill passes are, most likely, bluffs

After the bill was introduced, three well-known pro-Beijing political figures in Hong Kong made a rather startling threat: That if the U.S. sanctions judges and prosecutors, the Chinese government could respond by transferring political prisoners to Mainland China under Article 55 of the National Security Law.

In other words, they threatened to retaliate against the United States by treating political prisoners in their custody the way terrorists treat hostages—not exactly the best message to send when you’re trying to convince the world that you should be treated as an international financial center with rule of law.

The three officials who made these threats—non-official convenor of the Executive Council Regina Ip, retired National People’s Congress Standing Committee member Tam Yiu-chung, and pro-Beijing thinktank personality Lau Siu-kai—did so in three separate comments, with Lau first speaking on a radio show, followed by Ip while leading her political party in a protest, and then Tam on a separate radio program.

National Security Law Article 55 permits Beijing to order such a transfer either at the request of the Hong Kong government or of its own accord. Upon transfer, they would be subject to China’s “justice” system, which is even more unjust than Hong Kong’s—secret trials without access to independent lawyers, no due process rights, and harsh sentences in difficult conditions. Beijing has not yet used this clause, no doubt because of the global outrage it would cause just as Hong Kong seeks to “normalize” its international status.

Understandably given the provocative nature of the comments, the threats received a great deal of press in both Chinese and English media. But while any such threats should be treated seriously, they are unlikely to be carried out.

For one thing, the remarks were made by three figures who are not considered to currently be in the inner circle of decision-makers. Tam is retired. Lau Siu-kai is an academic whose only official role is on a part time advisory committee of 56 experts and scholars called the Chief Executive’s Policy Unit.* And Ip holds a part time advisory position without a portfolio in the Executive Council after having failed at ingratiating herself with Beijing in her efforts to become Chief Executive.

As such, these fairly inconsequential figures are not the most likely prospects for Beijing to deliver such a serious threat.

What’s more, the manner of the threat’s delivery contrasts starkly with the coordinated statements and protests orchestrated by Beijing in response to the bill. Lau made the remark off-hand in a radio interview, and then it was echoed by Ip and Tam, also apparently after being asked about it by reporters. They do not appear to have prepared or coordinated on these statements.

It is more likely that these three figures were acting on their own in a dance we’ve seen more and more in Hong Kong’s ranks: performative efforts to impress Beijing by out-doing each other in the level of shock and attention they can bring to the cause.

Even if I’m wrong here and the threat did originate with Beijing or the Hong Kong government, actually carrying it out would make little sense. The crux of the accusation that forms the basis for the Hong Kong Sanctions Act is that the judiciary is no longer independent and political defendants cannot get a fair trial. If Beijing responded to the Act by interfering with the Hong Kong judicial process and transferring prisoners to Mainland China, they would simply confirm to the world that the U.S. government was right. It doesn’t fit Beijing’s narrative, and would cause more problems for them while solving none.

***

The Hong Kong Sanctions Act will not solve the ongoing crisis facing Hong Kong and its people, nor will it get our political prisoners released and safe from harm. It is, nonetheless, an important step towards accountability for the officials contributing to the persecution of pro-democracy dissidents, and would serve as a strong warning to those who might seek to join in that persecution down the road.

If anyone still believes that sanctions can’t have an impact, Hong Kong’s over-the-top reaction to the mere prospect of new sanctions should prove otherwise.

*Corrected to note Lau Siu Kai’s current advisory role

Keen observation! From China's point of view, it is much more convenient to let Hong Kong's judiciary do all the dirty work for them.